Birds See Complete Birds List

| Mammals |

Amphibians | Reptiles |

Popular Posts

-

The cherry blossom (sakura) is Japan's unofficial national flower. It has been celebrated for many centuries and holds a very prom...

-

Setting foot in Lawang Sewu, Semarang, you sense not only the remnants of a bygone beauty, but also a mystical atmosphere. Entering Lawan...

-

As seductive as the south of France is in summer, we kind of like it off-season too. Maybe even prefer it. Domestic holidaymakers, internati...

North America Animal Facts

With its rivers and waterfalls, lakes and wetlands, springs, geysers, and caves, all rimmed with rocky seacoasts, sandy beaches, corals, and deltas, North America's 5.8 billion acres boast an amazing abundance and diversity of wildlife and wild lands. Unfortunately, many of them—like the black-footed ferret, its prairie dog prey, and their grassland habitat—are highly endangered.

The Unique Characteristics of Primates

General Characteristics

Taxonomy is the science of classification of organisms. Primates are difficult to classify. Most scientists classify primates, monkeys, and apes in the Kingdom Animalia, the Phylum Chordata (animals with a supporting rod along the back, this also includes sharks and rays), Subphylum Vertebrata (animals with a bony backbone), the Class Mammalia, and the Order Primates. As of 2004, there are 363 species of primates. In addition to monkeys and apes, the order includes prosimians ("premonkeys") such as lemurs and bushbabies as well as humans.

As mammals, primates possess the mammalian characteristics of endothermy (internal regulation of body temperature, often known as warm-bloodedness), bearing live young (placental), and feeding their young with milk produced by mammary glands.

As mammals, primates possess the mammalian characteristics of endothermy (internal regulation of body temperature, often known as warm-bloodedness), bearing live young (placental), and feeding their young with milk produced by mammary glands.

Not all primates possess the same characteristics—there is no unique characteristic that defines a primate. Most shared characteristics and trends are not derived but instead are a retention of ancestral features, which also adds difficulty to classifying primates. Many of these characteristics are behavioral, or depend on soft tissue anatomy; this does not help in identifying fossil primates. This retention of a fairly generalized body type, unlike hoof stock for example, reflects their diversity of life style. Their unspecialized morphology and highly flexible behavior allows them to fill many niches and adapt to environmental change.

There is a number of rather specific primate characteristics, such as details of the bones of the foot and skull. However, these characteristics do not make it easy for scientists to categorize early mammals and primates. There are a few scientists who consider tree shrews primates and bats the closest living relative to primates.

Some distinguishing characteristics of primates include:

* Forward-facing eyes for binocular vision (allowing depth perception)

* Increased reliance on vision: reduced noses, snouts (smaller, flattened), loss of vibrissae (whiskers), and relatively small, hairless ears

* Color vision

* Opposable thumbs for power grip (holding on) and precision grip (picking up small objects)

* Grasping fingers aid in power grip

* Flattened nails for fingertip protection, development of very sensitive tactile pads on digits

* Primitive limb structure, one upper limb bone, two lower limb bones, many mammalian orders have lost various bones, especially fusing of the two lower limb bones

* Generalist teeth for an opportunistic, omnivorous diet; loss of some primitive mammalian dentition, humans have lost two premolars

* Progressive expansion and elaboration of the brain, especially of the cerebral cortex

* Greater facial mobility and vocal repertoire

* Progressive and increasingly efficient development of gestational processes

* Prolongation of postnatal life periods

* Reduced litter size—usually just one (allowing mobility with clinging young and more individual attention to young)

* Most primates have one pair of mammae in the chest

* Complicated social organization

The Order Primates is divided into two Suborders: Strepsirhini, the lemurs and lorises, and the Haplorhini, the monkeys and apes.

1. Suborder Strepsirhini

The first primate like animal appeared around 70 million years ago. These are described as early prosimians. These earliest primates were nocturnal and arboreal, and many of the distinguishing characteristics of primates are actually associated with a night life in the trees. These characteristics were retained and have contributed to the success of primate lines that descended into terrestrial habitats. There are no prosimians in the New World, instead their nocturnal, insectivorous niche is taken up by other mammals, such as opossums. Strepsirhines include the lemurs on Lemur Island and in the Small Mammal House as well as lorises and bushbabies.

Some Strepsirhini characteristics include:

* Wet, naked, glandular nostrils (the rhinarium)

* Wet, naked, glandular nostrils (the rhinarium)

* Most are nocturnal

* Prominent whiskers

* Large, mobile ears

* Large eyes adapted for a nocturnal lifestyle, tapetum lucidum, a layer of reflective tissue behind the retina, which reflects light back toward the pupil, making the eyes visible in the dark, similar to a cat’s eye

* Gap in the upper border of each nostril

* Highly developed sense of smell

* Divided upper lip attached to gums by a membrane

* Dog-like faces, protruding snout (rostrum)

* Specialized scent glands, to allow for non-visual communication

* Tooth comb from lower incisors and canines

* Orbital bar

* Locomotor specializations: vertical clinging and leaping, slow quadrupedalism

* Grooming claw on second digit of foot and flat nails everywhere else

* Simple placenta

*Note: Most taxonomists have reclassified Prosimii as the suborder Strepsirhini. As the above list of characteristics show Strepsirhini exhibit more “primitive” characteristics. Anthropoidea and Tarsiodea, which were once included as prosimians, are now combined to form the Suborder Haplorhini or animals with a simple, dry nose.

The living Strepsirhini are divided into two main infraorders; the Lemuriformes, which contain the lemurs, dwarf lemurs, sifakas, and aye-ayes; and the Lorisiformes, the lorises and bushbabies.

2. Suborder Haplorhini

The haplorhines are considered the “higher” primates. This suborder includes all great apes, monkeys, tarsiers, and humans. Scientists believe that haplorhines first appeared in the Eocene, or 50 million years ago. These are the ancestors of today’s monkeys and apes.

Some Haplorhini characteristics include:

* The rhinarium is dry; nostrils are more rounded and continuous

* The upper lip is continuous and not attached to gums

* Free upper lip allows for more expressive face

* Eyes lack tapetum and do not reflect light

* Larger brain

* Reduced snout and less reliant on sense of smell

* Binocular and stereoscopic vision

* Delayed sexual maturity

* Usually one offspring, with extended maternal care

* Extended life span

* Trend towards longer arms than legs

The living haplorhines are divided into three infraorders the Tarsiiformes, or tarsiers, a very controversial group; the Platyrrhini, or New World monkeys; and the Catarrhini, or Old World monkeys, apes and humans.

Infraorder Tarsiiformes

Tarsiers display many characteristics of both prosimians and anthropoids; these terms are no longer used as true taxonomic categories, but are often used instead of Haplorhini and Strepsirhini when discussing basic morphology. As mentioned in the above note, the position of the tarsiers is still a question in primatology. However, it has been largely resolved by a change of nomenclature. “Rhine” means nose, in Greek, and generally refers to the specific nasal anatomy that can be used to distinguish these groups. Strepsirhines have dog-like, wet noses, whereas the rest of the primates have simple, dry noses. Tarsiers have a simple, dry nose. Therefore, prosimians become Strepsirhini and anthropoids become Haplorhini. By this definition, tarsiers become haplorhines, and the problem no longer exists.

The only genus in this group is Tarsius, or tarsiers. They are considered living fossils being the nearest relatives to the Haplorhini ancestors. They have changed very little and show characteristics of both prosimians and anthropoids. Like prosimians, they have a simple digestive tract, are nocturnal insectivores, have legs built for leaping and use grooming claws. Like anthropoids, they have a complete ocular orbit, a more advanced placenta, lack both a dental comb and the tapetum lucidum in their eyes. They also show a relatively larger brain than prosimians.

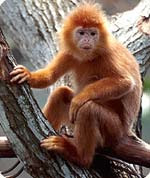

Infraorder Platyrrhini

The platyrrhines are also known as the New World monkeys. This includes all animals living in both Central and South America, from tamarins and marmosets to howlers and spider monkeys. There are no living non-human primates in North America, even though this is where some of the oldest primate fossils have been found. Scientists do not know the reason for this.

South America was isolated from the rest of the world in the Eocene and Oligocene, 40 and 25 million years ago. It seems to have been colonized by early anthropoids, either from Africa or North America via some sort of land bridge, or floating vegetation raft about 40 million years ago. These monkeys have evolved independently from that time on. New World monkeys are every bit as advanced as Old World monkeys with some very impressive adaptations that Old World monkeys lack, such as a prehensile tail.

The word platyrrhini, again describes the nose. Platyrrhines all have broad, flat noses and outward directed nasal openings. Platyrrhini is divided into two families the Cebidae, or monkeys, and the Callitrichidae, or tamarins and marmosets. Tamarins, marmosets, howler monkeys, and pale-headed saki monkeys.

Some Platyrrhini characteristics include:

* Outward facing, broad nostrils, flat, dry nose

* All but one genus, the owl monkeys, are diurnal

* Lack a bony tube between eardrum and outer ear

* Large brains and highly developed vision

* They are intelligent and active animals

* Many exhibit developed social structures and family groups

* Some have special scent glands

* Lack ischial callosities (bare patches of skin on rump)

* Imperfect opposability of thumb and poorly developed finger grip

* The big toe is large and strongly opposable

* Long, well developed tail, prehensile in some groups

* Some groups are fantastically arboreal, using their tail as a fifth limb

* There are no terrestrial New World monkeys

* Cebidae have fingernails instead of claws, which aid in gripping

* Callitrichidae have claws, modified nails, that aid in climbing tree trunks

* Three premolars

Infraorder Catarrhini

The catarrhines include all other primates, or Old World monkeys, apes and humans. Like the word Platyrrhini, Catarrhini refers to the shape of the nose and means down-facing nose. The nostrils are narrow, close together, and face downward. This infraorder is usually divided into two superfamilies, the Cercopithecoidea, or Old World monkeys, and the Hominoidea, or apes and humans.

Some Catarrhini characteristics include:

* Downward facing, narrow nostrils, short, dry nose

* Downward facing, narrow nostrils, short, dry nose

* Lack prominent whiskers

* Bony tube between eardrum and outer ear present

* Large brain

* Diurnal

* Greater sexual dimorphism: large canines, size, and coloration

* Complicated social structure

* Two premolars, one a sectorial premolar, meaning that it sharpens the upper canine

* Well-developed grip and opposable thumb and big toe, except humans

* Short or no tail

* Many terrestrial species

Superfamily Hominoidea

This superfamily contains humans and their close relatives, the apes. The first hominoids first appeared about 25 million years ago. Present-day hominoids are characterized by the absence of tails and by rather primitive rounded molars. This means that hominoid molars are less specialized than other primates.

Some Hominoid characteristics include:

* Large brain

* Large size

* Long arms

* Long curved fingers

* Very stable elbow joint

* Relatively spherical humerus head that allows for 360-degree shoulder rotation

* High limb mobility

* Long and robust clavicle

* Bony broad sternum

* Short and stable lumbar region of the back

* Broad pelvis

* No tail

* Primitive rounded molars

Most primatologists divide the Superfamily Hominoidea into two families, the Hylobatidae, or gibbons and siamangs, and the Hominidae, the humans and great apes. This division is still under debate. Some feel that similarities between human and ape DNA warrant classification in the same family. Others feel that human’s social and cognitive abilities place them in a family of their own, separate from the apes.

Family Hylobatidae

This family contains the gibbons and siamangs. They are the smallest and most numerous of the apes, (excluding humans). Because of their size hylobatids are sometimes referred to as lesser apes. They exhibit very little sexual dimorphism, although sex-specific color can be seen in white-cheeked gibbons. Males are nearly all black, while females are blond. They also have primitive or generalist molars. Relative to body size they have particularly long arms and are by far the best primate brachiators.

Some Hylobatidae characteristics include:

* Long forearms and arms, relative to body size

* Ischial callosities, or bare skin on rumps

* The only hominoid that does not build sleeping nests

* Omnivorous, but eats mostly fruit

* Territorial

* Live in monogamous pairs

* Some have enlarged throat sacs used when calling

* Largest canines of the apes

* Found only in the tropical forests of Southeast Asia

* Large brain and eye orbits

* Arm and shoulder girdle built for suspension

* Highly arboreal

Family Hominidae

This family includes chimpanzees, orangutans, gorillas, bonobos, and hominins. Early hominids appeared about 20 million years ago in Africa and Asia. Hominids, or humans, appeared about five million years ago in Africa. Hominids range in weight from about 100 to 500 pounds (48 to 227 kg). Males are larger than females.

Some Hominidae characteristics include:

* Larger brain

* Complex social behaviors, including complex vocalizations

* Larger body size

* Mostly terrestrial, only orangutans are really arboreal

* Sexual dimorphism

* Opposable thumbs and big toes, except in humans, whose big toes are not opposable

* All digits have flattened nails

* Lack ischial callosities

* Many skeletal differences from other primates related to their upright/semi-upright posture

* 32 teeth, including two premolars

* All, but humans, are good climbers

* Make and use nests

* Prolonged period of parental care

* Birth of a single young

References

Stein, Philip and Bruce Rowe. Physical Anthropology: The Core. McGraw-Hill, Inc. New York. 1995

University of California, Davis, Department of Anthropology, The Strepsirhini and Tarsiiformes, Fall 1999, Ant 154

Harvard University, B-27 Human Evolution, Spring 2001, Pibeam, Steiper, Mallol

University of Leeds, Primate Taxonomy, Dr. Bill Sellers

University of Michigan, Museum of Zoology, Animal Diversity Web, Order Primates, 1999, Phil Myers

University of Michigan, Museum of Zoology, Animal Diversity Web, Cebidae, 1999, Phil Myers

University of Michigan, Museum of Zoology, Animal Diversity Web, Callitrichidae, 1999, Nancy Shefferly and Phil Myers

University of Michigan, Museum of Zoology, Animal Diversity Web, Hylobatidae, 1999, Phil Myers

University of Michigan, Museum of Zoology, Animal Diversity Web, Hominidae, 1999, Phil Myers

University of Texas, Austin, Department of Anthropology, Primates as an Adaptive Array, May 2001

University of Vermont, Department of Biology, Order Primates: Introduction, Strepsirhini: Lemuriformes and Lorisiformes, Jan Decher

University of Vermont, Department of Biology, Order Primates: SO Haplorhini: Tarsiiformes, Platyrrhini, Jan Decher,

University of Vermont, Department of Biology, Order Primates: SO Haplorhini II: Catarrhini, Jan Decher,

University of Vermont, Department of Biology, Order Primates: SO Haplorhini, IO Catarrhini: Hominoidea, Jan Decher,

University of Wisconsin-Madison, Wisconsin Regional Primate Research Center, Primate Fact Sheets, Sean Flannery, 2001

Taxonomy is the science of classification of organisms. Primates are difficult to classify. Most scientists classify primates, monkeys, and apes in the Kingdom Animalia, the Phylum Chordata (animals with a supporting rod along the back, this also includes sharks and rays), Subphylum Vertebrata (animals with a bony backbone), the Class Mammalia, and the Order Primates. As of 2004, there are 363 species of primates. In addition to monkeys and apes, the order includes prosimians ("premonkeys") such as lemurs and bushbabies as well as humans.

As mammals, primates possess the mammalian characteristics of endothermy (internal regulation of body temperature, often known as warm-bloodedness), bearing live young (placental), and feeding their young with milk produced by mammary glands.

As mammals, primates possess the mammalian characteristics of endothermy (internal regulation of body temperature, often known as warm-bloodedness), bearing live young (placental), and feeding their young with milk produced by mammary glands.Not all primates possess the same characteristics—there is no unique characteristic that defines a primate. Most shared characteristics and trends are not derived but instead are a retention of ancestral features, which also adds difficulty to classifying primates. Many of these characteristics are behavioral, or depend on soft tissue anatomy; this does not help in identifying fossil primates. This retention of a fairly generalized body type, unlike hoof stock for example, reflects their diversity of life style. Their unspecialized morphology and highly flexible behavior allows them to fill many niches and adapt to environmental change.

There is a number of rather specific primate characteristics, such as details of the bones of the foot and skull. However, these characteristics do not make it easy for scientists to categorize early mammals and primates. There are a few scientists who consider tree shrews primates and bats the closest living relative to primates.

Some distinguishing characteristics of primates include:

* Forward-facing eyes for binocular vision (allowing depth perception)

* Increased reliance on vision: reduced noses, snouts (smaller, flattened), loss of vibrissae (whiskers), and relatively small, hairless ears

* Color vision

* Opposable thumbs for power grip (holding on) and precision grip (picking up small objects)

* Grasping fingers aid in power grip

* Flattened nails for fingertip protection, development of very sensitive tactile pads on digits

* Primitive limb structure, one upper limb bone, two lower limb bones, many mammalian orders have lost various bones, especially fusing of the two lower limb bones

* Generalist teeth for an opportunistic, omnivorous diet; loss of some primitive mammalian dentition, humans have lost two premolars

* Progressive expansion and elaboration of the brain, especially of the cerebral cortex

* Greater facial mobility and vocal repertoire

* Progressive and increasingly efficient development of gestational processes

* Prolongation of postnatal life periods

* Reduced litter size—usually just one (allowing mobility with clinging young and more individual attention to young)

* Most primates have one pair of mammae in the chest

* Complicated social organization

The Order Primates is divided into two Suborders: Strepsirhini, the lemurs and lorises, and the Haplorhini, the monkeys and apes.

1. Suborder Strepsirhini

The first primate like animal appeared around 70 million years ago. These are described as early prosimians. These earliest primates were nocturnal and arboreal, and many of the distinguishing characteristics of primates are actually associated with a night life in the trees. These characteristics were retained and have contributed to the success of primate lines that descended into terrestrial habitats. There are no prosimians in the New World, instead their nocturnal, insectivorous niche is taken up by other mammals, such as opossums. Strepsirhines include the lemurs on Lemur Island and in the Small Mammal House as well as lorises and bushbabies.

Some Strepsirhini characteristics include:

* Wet, naked, glandular nostrils (the rhinarium)

* Wet, naked, glandular nostrils (the rhinarium)* Most are nocturnal

* Prominent whiskers

* Large, mobile ears

* Large eyes adapted for a nocturnal lifestyle, tapetum lucidum, a layer of reflective tissue behind the retina, which reflects light back toward the pupil, making the eyes visible in the dark, similar to a cat’s eye

* Gap in the upper border of each nostril

* Highly developed sense of smell

* Divided upper lip attached to gums by a membrane

* Dog-like faces, protruding snout (rostrum)

* Specialized scent glands, to allow for non-visual communication

* Tooth comb from lower incisors and canines

* Orbital bar

* Locomotor specializations: vertical clinging and leaping, slow quadrupedalism

* Grooming claw on second digit of foot and flat nails everywhere else

* Simple placenta

*Note: Most taxonomists have reclassified Prosimii as the suborder Strepsirhini. As the above list of characteristics show Strepsirhini exhibit more “primitive” characteristics. Anthropoidea and Tarsiodea, which were once included as prosimians, are now combined to form the Suborder Haplorhini or animals with a simple, dry nose.

The living Strepsirhini are divided into two main infraorders; the Lemuriformes, which contain the lemurs, dwarf lemurs, sifakas, and aye-ayes; and the Lorisiformes, the lorises and bushbabies.

2. Suborder Haplorhini

The haplorhines are considered the “higher” primates. This suborder includes all great apes, monkeys, tarsiers, and humans. Scientists believe that haplorhines first appeared in the Eocene, or 50 million years ago. These are the ancestors of today’s monkeys and apes.

Some Haplorhini characteristics include:

* The rhinarium is dry; nostrils are more rounded and continuous

* The upper lip is continuous and not attached to gums

* Free upper lip allows for more expressive face

* Eyes lack tapetum and do not reflect light

* Larger brain

* Reduced snout and less reliant on sense of smell

* Binocular and stereoscopic vision

* Delayed sexual maturity

* Usually one offspring, with extended maternal care

* Extended life span

* Trend towards longer arms than legs

The living haplorhines are divided into three infraorders the Tarsiiformes, or tarsiers, a very controversial group; the Platyrrhini, or New World monkeys; and the Catarrhini, or Old World monkeys, apes and humans.

Infraorder Tarsiiformes

Tarsiers display many characteristics of both prosimians and anthropoids; these terms are no longer used as true taxonomic categories, but are often used instead of Haplorhini and Strepsirhini when discussing basic morphology. As mentioned in the above note, the position of the tarsiers is still a question in primatology. However, it has been largely resolved by a change of nomenclature. “Rhine” means nose, in Greek, and generally refers to the specific nasal anatomy that can be used to distinguish these groups. Strepsirhines have dog-like, wet noses, whereas the rest of the primates have simple, dry noses. Tarsiers have a simple, dry nose. Therefore, prosimians become Strepsirhini and anthropoids become Haplorhini. By this definition, tarsiers become haplorhines, and the problem no longer exists.

The only genus in this group is Tarsius, or tarsiers. They are considered living fossils being the nearest relatives to the Haplorhini ancestors. They have changed very little and show characteristics of both prosimians and anthropoids. Like prosimians, they have a simple digestive tract, are nocturnal insectivores, have legs built for leaping and use grooming claws. Like anthropoids, they have a complete ocular orbit, a more advanced placenta, lack both a dental comb and the tapetum lucidum in their eyes. They also show a relatively larger brain than prosimians.

Infraorder Platyrrhini

The platyrrhines are also known as the New World monkeys. This includes all animals living in both Central and South America, from tamarins and marmosets to howlers and spider monkeys. There are no living non-human primates in North America, even though this is where some of the oldest primate fossils have been found. Scientists do not know the reason for this.

South America was isolated from the rest of the world in the Eocene and Oligocene, 40 and 25 million years ago. It seems to have been colonized by early anthropoids, either from Africa or North America via some sort of land bridge, or floating vegetation raft about 40 million years ago. These monkeys have evolved independently from that time on. New World monkeys are every bit as advanced as Old World monkeys with some very impressive adaptations that Old World monkeys lack, such as a prehensile tail.

The word platyrrhini, again describes the nose. Platyrrhines all have broad, flat noses and outward directed nasal openings. Platyrrhini is divided into two families the Cebidae, or monkeys, and the Callitrichidae, or tamarins and marmosets. Tamarins, marmosets, howler monkeys, and pale-headed saki monkeys.

Some Platyrrhini characteristics include:

* Outward facing, broad nostrils, flat, dry nose

* All but one genus, the owl monkeys, are diurnal

* Lack a bony tube between eardrum and outer ear

* Large brains and highly developed vision

* They are intelligent and active animals

* Many exhibit developed social structures and family groups

* Some have special scent glands

* Lack ischial callosities (bare patches of skin on rump)

* Imperfect opposability of thumb and poorly developed finger grip

* The big toe is large and strongly opposable

* Long, well developed tail, prehensile in some groups

* Some groups are fantastically arboreal, using their tail as a fifth limb

* There are no terrestrial New World monkeys

* Cebidae have fingernails instead of claws, which aid in gripping

* Callitrichidae have claws, modified nails, that aid in climbing tree trunks

* Three premolars

Infraorder Catarrhini

The catarrhines include all other primates, or Old World monkeys, apes and humans. Like the word Platyrrhini, Catarrhini refers to the shape of the nose and means down-facing nose. The nostrils are narrow, close together, and face downward. This infraorder is usually divided into two superfamilies, the Cercopithecoidea, or Old World monkeys, and the Hominoidea, or apes and humans.

Some Catarrhini characteristics include:

* Downward facing, narrow nostrils, short, dry nose

* Downward facing, narrow nostrils, short, dry nose* Lack prominent whiskers

* Bony tube between eardrum and outer ear present

* Large brain

* Diurnal

* Greater sexual dimorphism: large canines, size, and coloration

* Complicated social structure

* Two premolars, one a sectorial premolar, meaning that it sharpens the upper canine

* Well-developed grip and opposable thumb and big toe, except humans

* Short or no tail

* Many terrestrial species

Superfamily Hominoidea

This superfamily contains humans and their close relatives, the apes. The first hominoids first appeared about 25 million years ago. Present-day hominoids are characterized by the absence of tails and by rather primitive rounded molars. This means that hominoid molars are less specialized than other primates.

Some Hominoid characteristics include:

* Large brain

* Large size

* Long arms

* Long curved fingers

* Very stable elbow joint

* Relatively spherical humerus head that allows for 360-degree shoulder rotation

* High limb mobility

* Long and robust clavicle

* Bony broad sternum

* Short and stable lumbar region of the back

* Broad pelvis

* No tail

* Primitive rounded molars

Most primatologists divide the Superfamily Hominoidea into two families, the Hylobatidae, or gibbons and siamangs, and the Hominidae, the humans and great apes. This division is still under debate. Some feel that similarities between human and ape DNA warrant classification in the same family. Others feel that human’s social and cognitive abilities place them in a family of their own, separate from the apes.

Family Hylobatidae

This family contains the gibbons and siamangs. They are the smallest and most numerous of the apes, (excluding humans). Because of their size hylobatids are sometimes referred to as lesser apes. They exhibit very little sexual dimorphism, although sex-specific color can be seen in white-cheeked gibbons. Males are nearly all black, while females are blond. They also have primitive or generalist molars. Relative to body size they have particularly long arms and are by far the best primate brachiators.

Some Hylobatidae characteristics include:

* Long forearms and arms, relative to body size

* Ischial callosities, or bare skin on rumps

* The only hominoid that does not build sleeping nests

* Omnivorous, but eats mostly fruit

* Territorial

* Live in monogamous pairs

* Some have enlarged throat sacs used when calling

* Largest canines of the apes

* Found only in the tropical forests of Southeast Asia

* Large brain and eye orbits

* Arm and shoulder girdle built for suspension

* Highly arboreal

Family Hominidae

This family includes chimpanzees, orangutans, gorillas, bonobos, and hominins. Early hominids appeared about 20 million years ago in Africa and Asia. Hominids, or humans, appeared about five million years ago in Africa. Hominids range in weight from about 100 to 500 pounds (48 to 227 kg). Males are larger than females.

Some Hominidae characteristics include:

* Larger brain

* Complex social behaviors, including complex vocalizations

* Larger body size

* Mostly terrestrial, only orangutans are really arboreal

* Sexual dimorphism

* Opposable thumbs and big toes, except in humans, whose big toes are not opposable

* All digits have flattened nails

* Lack ischial callosities

* Many skeletal differences from other primates related to their upright/semi-upright posture

* 32 teeth, including two premolars

* All, but humans, are good climbers

* Make and use nests

* Prolonged period of parental care

* Birth of a single young

References

Stein, Philip and Bruce Rowe. Physical Anthropology: The Core. McGraw-Hill, Inc. New York. 1995

University of California, Davis, Department of Anthropology, The Strepsirhini and Tarsiiformes, Fall 1999, Ant 154

Harvard University, B-27 Human Evolution, Spring 2001, Pibeam, Steiper, Mallol

University of Leeds, Primate Taxonomy, Dr. Bill Sellers

University of Michigan, Museum of Zoology, Animal Diversity Web, Order Primates, 1999, Phil Myers

University of Michigan, Museum of Zoology, Animal Diversity Web, Cebidae, 1999, Phil Myers

University of Michigan, Museum of Zoology, Animal Diversity Web, Callitrichidae, 1999, Nancy Shefferly and Phil Myers

University of Michigan, Museum of Zoology, Animal Diversity Web, Hylobatidae, 1999, Phil Myers

University of Michigan, Museum of Zoology, Animal Diversity Web, Hominidae, 1999, Phil Myers

University of Texas, Austin, Department of Anthropology, Primates as an Adaptive Array, May 2001

University of Vermont, Department of Biology, Order Primates: Introduction, Strepsirhini: Lemuriformes and Lorisiformes, Jan Decher

University of Vermont, Department of Biology, Order Primates: SO Haplorhini: Tarsiiformes, Platyrrhini, Jan Decher,

University of Vermont, Department of Biology, Order Primates: SO Haplorhini II: Catarrhini, Jan Decher,

University of Vermont, Department of Biology, Order Primates: SO Haplorhini, IO Catarrhini: Hominoidea, Jan Decher,

University of Wisconsin-Madison, Wisconsin Regional Primate Research Center, Primate Fact Sheets, Sean Flannery, 2001

Differences Among Primates

There are more than 350 species of primates, varying in size from the pygmy mouse lemur (weighing about an ounce) to gorillas (males can weigh up to 600 pounds). Most live in the tropics or subtropics, and most depend on forests for their survival. Primates share characteristics—such as five-fingered hands with opposing thumbs, forward-facing eyes, and color vision—but they do vary greatly, especially from prosimian to monkey to ape.

| Prosimians | Monkeys | Apes |

|

|

|

Gorilla

Order: Primates

Order: PrimatesInfraorder: Catarrhini

Family: Hominidae

Species: Gorilla gorilla

Subspecies:

G. g. gorilla (western lowland)

G. g. diehli (Cross River)

Species: Gorilla beringei

Subspecies:

G. b. beringei (mountain)

G. b. graueri (eastern lowland)

Some primatologists list one additional subspecies of mountain gorilla, and are proposing to separate the Bwindi population into a fifth gorilla subspecies.

Shy vegetarians, the world's largest primates face an uncertain future in Africa's remaining equatorial forests.

Physical Description

Gorilla of different subspecies vary in coat length, hair color, and jaw and teeth size. Individuals vary, but many western lowland gorillas (G. g. gorilla) have brownish-gray coats, unlike the often blackish coats of the mountain (G. b. beringei) and eastern lowland (G. b. graueri) gorillas.

Generally, the mountain gorilla has longer hair than the other subspecies.

Western lowland gorillas have a more pronounced brow ridge, and ears that appear small in relation to their heads. They also have a different shaped nose and lip. Adult male gorillas’ heads look conical due to the large bony crests on the top (sagittal) and back (nuchal) of the skull. These crests anchor the massive muscles used to support and operate their large jaws and teeth. Adult female gorillas also have these crests, but they are much less pronounced. In comparison to the mountain gorilla, the western lowland gorilla has a wider and larger skull and the big toe of the western lowland gorilla is spread apart more from the alignment of his other four toes.

Like all great apes, gorillas’ arms are longer than their legs. When they move quadrupedally, they knuckle-walk, supporting their weight on the third and fourth digits of their curled hands. Like other primates each individual has distinctive fingerprints.

Like all great apes, gorillas’ arms are longer than their legs. When they move quadrupedally, they knuckle-walk, supporting their weight on the third and fourth digits of their curled hands. Like other primates each individual has distinctive fingerprints.Lowland gorilla hair is short, soft, and very fine. There is no under fur (a thick layer of insulating hair close to the skin, such as on dogs or minks). Lowland gorillas’ coats are suited for warm, moist forest habitats. Mountain gorillas are more shaggy and thick-furred due to the colder temperatures at high altitudes.

Size

The eastern lowland gorilla is the largest. Adult male gorillas have silvery white "saddles" that inspired the name "silverback" for these animals.

On two legs, adult male gorillas stand about five a half feet tall (rarely a bit taller). They weigh between 300 and 400 pounds. Females are smaller, standing up to five feet tall and averaging about 200 pounds. Zoo animals are often heavier.

Geographic Distribution

Western lowland gorillas live in lowland tropical forests in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Angola, and Nigeria.

Eastern lowland gorillas, also called Grauer's gorillas, live in tropical forests from low elevations up to 8,000 feet in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire) and along the border with Uganda and Rwanda.

Mountain gorillas, the rarest of the subspecies, hang on in mountain forests (up to 11,000 feet) at the borders of Rwanda, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Status

Western lowland and Cross River gorillas are listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Eastern lowland and mountain gorillas are listed as endangered on the Red List.

Habitat

Gorillas live in moist tropical forests, often in secondary, or re-growing, forests or along forest edges, where clearings provide an abundance of low, edible vegetation. Mountain gorillas range up into cloud forest.

Diet in the Wild

Gorillas are primarily herbivorous, eating the leaves and stems of herbs, shrubs, and vines. In some areas, they raid farms, eating and trampling crops. They also will eat rotten wood and small animals.

The diet of western lowland gorillas also includes the fleshy fruits of close to a hundred seasonally fruiting tree species; the diets of other gorilla subspecies include proportionally less fruit. Gorillas get some protein from invertebrates found on leaves and fruits. Adult male gorillas eat about 45 pounds (32 kg) of food per day. Females eat about two-thirds of that amount.

Reproduction

Female gorillas reach maturity at seven or eight years old, but they usually don't breed until ten years or older.

Due to competition between males for access to females, few wild males breed before they reach 15 years old. Eight and a half months after mating, a female gives birth to one young, which can usually walk within three to six months. Young are usually weaned by three years old, and females can give birth every four years.

Upon reaching sexual maturity, between ages seven and ten, young gorillas strike out on their own, seeking new groups or mates. Zoo gorillas may reach sexual maturity before seven years old, and may have young every two to three years.

Life Span

Gorillas may live about 35 years in the wild, and up to 54 in zoos.

Behavior

Gorillas live in groups. Each group usually contains one or more silverbacks and two to ten females and young. Newly established silverbacks may kill young not sired by them, but otherwise, gorilla family life is mostly peaceful. Bloody battles sometimes occur between silverbacks when they square off to compete over female groups or home ranges. Gorillas spend their mornings and evenings feeding, usually covering only a small area of forest at a time. Groups spend the middle of the day sleeping, playing, or grooming (females groom their young or a silverback). At night, gorillas fashion nests of leaves and branches on which to sleep; unweaned infants sleep in their mothers' nests.

Social Structure

Gorillas are behaviorally flexible. This means that their behavior and social structure is not set in stone; there is great variety. The information below should only be used as a general guide.

Gorillas live in groups, or troops, from two to more than 30 members. Western lowland data seem to indicate smaller group sizes, averaging about five individuals. Groups are generally composed of a silverback male, one or more black back males, several adult females, and their infant and juvenile offspring. This group composition varies greatly due to births and deaths and to the immigration and emigration of individuals.

Mature offspring typically leave their natal group to find a mate. At about eight years old, females generally emigrate into a new group of her choosing. She seems to choose which silverback to join based on such attributes as size and quality of his home range, etc. This seems to be related to the silverback’s size, but not always. A female may change family groups a number of times throughout her life. When leaving their natal group, some sexually mature males may attempt to replace the silverback in an already established group. However, they usually spend a few years as solitary males. Nevertheless, a new troop can be easily formed when one or more non-related females join a lone male.

The group is led by the adult, dominant, silverback male. He has exclusive breeding rights to the females. At times he may allow other sub-adult males in the group to mate with females. The silverback mediates disputes and also determines the group’s home range. He regulates what time they wake up, eat and go to sleep.

Gorillas are most active in the morning and late afternoon. They wake up just after sunrise to search for food, and then eat for several hours. Midday, adults take a siesta and usually nap in a day nest while the young wrestle and play games. After their midday nap they forage again. Before dusk each gorilla makes its own nest, infants nest with their mothers.

All gorillas over three years make nests, day nests for resting and night nests for sleeping. Infants share their mothers’ nests. Gorillas form nests by sitting in one place and pulling down and tucking branches, leaves, or other vegetation around themselves. Adult males usually nest on the ground. Females may nest on the ground or in trees. Juveniles are more apt to nest in trees. Studies of western lowland gorillas have shown that the number of nests found at a site does not necessarily coincide with the number of weaned animals observed in a group.

The western lowland gorilla is characterized as a quiet, peaceful, and non-aggressive animal. They never attack unless provoked. However, males do fight over acquisition and defense of females, and the new leader of a group may kill unrelated infants. This causes the females to begin cycling sooner. An adult male protecting his group may attempt to intimidate his aggressor by standing on his legs and slapping its chest with cupped or flat hands while roaring and screaming. If this elaborate display is unsuccessful and the intruder persists, the male may rear his head back violently several times. He may also drop on all fours and charge toward the intruder. In general, when they charge they do not hit the intruder. Instead, they merely pass them by. This demonstration of aggression maintains order among separate troops and reduces the possibility of injury. It is thought that size plays an important role in determining the winner of an encounter between males (the larger male wins). Because of gorilla variability, some or all of these behaviors may not be seen.

Gorillas exhibit complex and dynamic relationships. They interact using grooming behaviors, although less than most other primates. Also affiliation may be shown by physical proximity.

Young gorillas play often and are more arboreal than the large adults. Adults, even the silverback, tolerate infant play behavior. He also tolerates, to a lesser extent, and often participates in the play of older juveniles and black back males.

The duration and frequency of sexual activity in gorillas are low in comparison to other great apes. The silverback has exclusive mating rights with the adult females in his group. The reproductive success of males depends upon the maintenance of exclusive rights to adult females. The female chooses to mate with the silverback by emigrating into his family group. Normally quiet animals, some gorillas are unusually loud during copulation.

Communication

Gorillas communicate using auditory signals (vocalizations), visual signals (gestures, body postures, facial expressions), and olfactory signals (odors). They are generally quiet animals, grunting and belching, but they may also scream, bark, and roar. Dian Fossey heard 17 different kinds of sounds from mountain gorillas. Other scientists have heard 22 different vocalizations, each seeming to have its own meaning. Gorillas crouch low and approach from the side when they are being submissive. They walk directly when confident and stand, chest beat (actually they slap with open hands), and advance when being aggressive.

Past/Present/Future

Until several decades ago, gorilla populations enjoyed the seclusion of vast tracts of forest. Today, Africa's growing population puts many pressures on these declining primates. Logging roads snake into forests, opening frontiers to settlers and loggers, while hunters kill or capture gorillas for their meat, parts (sometimes sold as souvenirs), or because the animals raid farm fields. Gorilla meat is eaten by hunters and loggers, and is also sold in city markets and restaurants.

While protection laws exist in most countries still inhabited by gorillas, enforcement is often lacking. Civil wars in Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo have harmed conservation efforts in these countries and opened parks to poachers. Gorillas also stumble into snares set for other animals, and may be killed or injured. Increased political stability, better public awareness, and carefully protected parks would go a long way toward reversing the gorillas' decline.

Outbreaks of the Ebola virus and increased hunting led the IUCN to move the western lowland gorilla from endangered to critically endangered status in 2007. In August 2008, the Wildlife Conservation Society released a census showing that more than 125,000 western lowland gorillas are living in two adjacent areas of the northern part of the Republic of Congo. Previously, it was thought there could be fewer than 50,000 of these gorillas.

With a population of fewer than 300 individuals, Cross River gorillas are listed as critically endangered.

A Few Gorilla Neighbors

Leopard (Panthera pardus): The only animal in its range, aside from humans, that can harm an adult gorilla, although these animals rarely tangle with each other.

African elephant (Loxodonta africana): By downing trees, forest-dwelling elephants help create gorilla feeding areas.

African gray parrot (Psittacus erithacus): Despite a large range, this forest parrot is disappearing from many areas due to capture for the cage bird trade and forest cutting. By saving gorilla habitat, we protect these and many other animals.

Fun Facts

Despite their size and current popularity, gorillas remained a mystery to people living outside of Africa until a missionary described them in 1847. After chimpanzees, gorillas are our closest relatives, sharing about 98 percent of our genes.

Gibbon

Order: Primates

Suborder: Haplorhini

Infraorder: Catarrhini

Family: Hylobatidae

Physical Description

The 12 species of gibbons are classified, referring to their size, as lesser apes. They exhibit many of the general characteristics of primates: flat faces, stereoscopic vision, enlarged brain size, grasping hands and feet, and opposable digits; and many specific characteristics of apes: broad chest, full shoulder rotation, no tail, and arms longer than legs.

Gibbons are relatively small, slender, and agile. They have fluffy, dense hair. They are not sexually dimorphic in size. Mature females usually weigh more than mature males. They have very long arms, which they use in a spectacular arm-swinging locomotion called brachiation. Their hands and fingers are also very long. The relatively short thumb is set well down on the palm, and their fingers form a hook, which is used during brachiation. Gibbons have very good bipedal locomotion, which they use on stable surfaces too large to grasp. When walking bipedally, arms are held up to keep from dragging and to assist with balance. Gibbons are sometimes observed putting their weight on their hands and swinging their legs through as if using crutches.

Gibbons are relatively small, slender, and agile. They have fluffy, dense hair. They are not sexually dimorphic in size. Mature females usually weigh more than mature males. They have very long arms, which they use in a spectacular arm-swinging locomotion called brachiation. Their hands and fingers are also very long. The relatively short thumb is set well down on the palm, and their fingers form a hook, which is used during brachiation. Gibbons have very good bipedal locomotion, which they use on stable surfaces too large to grasp. When walking bipedally, arms are held up to keep from dragging and to assist with balance. Gibbons are sometimes observed putting their weight on their hands and swinging their legs through as if using crutches.

Gibbons do not build nests like the great apes. They sleep sitting up with their arms wrapped around their knees and their head tucked into their lap. They have ischial callosities (fleshy, nerveless pads attached to the hip bones, a characteristic otherwise found only in Old World monkeys).

Social Structure

Gibbons live in small, monogamous families composed of a mated pair and up to four offspring. Less than six percent of all primate species (more than 300) are considered monogamous.

Gibbons are one of the few apes where the adult female is the dominant animal in the group. The hierarchy places her female offspring next followed by the male offspring and finally by the adult male.

Gibbons are physically independent at about three, mature at about six, and usually leave the family group at about eight, though they may spend up to ten years in their family group.

Communication

Gibbons are known for their beautiful song. Their loud vocalization can be heard up to one mile away and is used to announce location, defend territory, and maintain bonds with the family unit. The adult pair, sometimes joined by practicing juveniles, sing duets. Each individual can be identified by his or her song.

Siamangs have a louder call than white-cheked gibbons, amplified by a throat sac. Their call can be heard up to two miles away. Also used to defend territory, it includes more of a boom, bark, and a loud call increasing in speed as the call goes on, as compared to the chatter and calling of the other gibbon families.

Life span

Longevity in the wild is 25 to 30 years and can be as long as 40 years in captivity.

Conservation

All gibbons are endangered, largely due to deforestation. They are also hunted and trapped for the pet trade.

Fact sheets for other gibbon species :

Suborder: Haplorhini

Infraorder: Catarrhini

Family: Hylobatidae

Physical Description

The 12 species of gibbons are classified, referring to their size, as lesser apes. They exhibit many of the general characteristics of primates: flat faces, stereoscopic vision, enlarged brain size, grasping hands and feet, and opposable digits; and many specific characteristics of apes: broad chest, full shoulder rotation, no tail, and arms longer than legs.

Gibbons are relatively small, slender, and agile. They have fluffy, dense hair. They are not sexually dimorphic in size. Mature females usually weigh more than mature males. They have very long arms, which they use in a spectacular arm-swinging locomotion called brachiation. Their hands and fingers are also very long. The relatively short thumb is set well down on the palm, and their fingers form a hook, which is used during brachiation. Gibbons have very good bipedal locomotion, which they use on stable surfaces too large to grasp. When walking bipedally, arms are held up to keep from dragging and to assist with balance. Gibbons are sometimes observed putting their weight on their hands and swinging their legs through as if using crutches.

Gibbons are relatively small, slender, and agile. They have fluffy, dense hair. They are not sexually dimorphic in size. Mature females usually weigh more than mature males. They have very long arms, which they use in a spectacular arm-swinging locomotion called brachiation. Their hands and fingers are also very long. The relatively short thumb is set well down on the palm, and their fingers form a hook, which is used during brachiation. Gibbons have very good bipedal locomotion, which they use on stable surfaces too large to grasp. When walking bipedally, arms are held up to keep from dragging and to assist with balance. Gibbons are sometimes observed putting their weight on their hands and swinging their legs through as if using crutches. Gibbons do not build nests like the great apes. They sleep sitting up with their arms wrapped around their knees and their head tucked into their lap. They have ischial callosities (fleshy, nerveless pads attached to the hip bones, a characteristic otherwise found only in Old World monkeys).

Social Structure

Gibbons live in small, monogamous families composed of a mated pair and up to four offspring. Less than six percent of all primate species (more than 300) are considered monogamous.

Gibbons are one of the few apes where the adult female is the dominant animal in the group. The hierarchy places her female offspring next followed by the male offspring and finally by the adult male.

Gibbons are physically independent at about three, mature at about six, and usually leave the family group at about eight, though they may spend up to ten years in their family group.

Communication

Gibbons are known for their beautiful song. Their loud vocalization can be heard up to one mile away and is used to announce location, defend territory, and maintain bonds with the family unit. The adult pair, sometimes joined by practicing juveniles, sing duets. Each individual can be identified by his or her song.

Siamangs have a louder call than white-cheked gibbons, amplified by a throat sac. Their call can be heard up to two miles away. Also used to defend territory, it includes more of a boom, bark, and a loud call increasing in speed as the call goes on, as compared to the chatter and calling of the other gibbon families.

Life span

Longevity in the wild is 25 to 30 years and can be as long as 40 years in captivity.

Conservation

All gibbons are endangered, largely due to deforestation. They are also hunted and trapped for the pet trade.

Fact sheets for other gibbon species :

White-cheeked Gibbons

Siamangs

Black Howler Monkey

Howler monkeys are named and known for the loud, guttural howls that they routinely use at the beginning and end of the day. They are the loudest animal in the New World and while their howl is not a piercing sound, it can travel for three miles through dense forest.

Black howler monkeys are inhabitants of Latin American rainforests, ranging through eastern Bolivia, southern Brazil and Paraguay, and northern Argentina. They are the largest monkey in Latin American rainforests; they grow to be about two to four feet tall and weigh from eight to twenty-two pounds. They have big necks and lower jaws, where their super-sized vocal cords are housed.

Male howler monkeys use their big voices to defend their turf. Howls by one troop are answered by other males within earshot. Every-one starts and ends the day by checking out where their nearest competitors are. In this way, they protect the food in their territory. It’s an important job because their diet is made up mostly of leaves—not a particularly nutritious food. Finding young, nutritious leaves is a priority. Fruit and flowers are also valued so it’s crucial that the troop stakes its claim on these treasures when they are found.

Interestingly, when there are few howler monkeys in an area, the howling routine takes on a different pattern. In Belize, where black howler monkeys were reintroduced into a wildlife sanctuary, the howler monkeys were heard only a few times a week rather than every day. Apparently, with plenty of space and no other howler monkeys, there was no need to check on the whereabouts of competitors. As the population grows and new troops are established, there will be more reason to check in with the neighbors.

Interestingly, when there are few howler monkeys in an area, the howling routine takes on a different pattern. In Belize, where black howler monkeys were reintroduced into a wildlife sanctuary, the howler monkeys were heard only a few times a week rather than every day. Apparently, with plenty of space and no other howler monkeys, there was no need to check on the whereabouts of competitors. As the population grows and new troops are established, there will be more reason to check in with the neighbors.Despite the volume of their howl, it’s disorienting to try to find a troop of loud howler monkeys in the wild. They hang out in the treetops where younger, greener leaves are abundant. However, if you do find yourself in the rainforest and it seems that an unusually large amount of fruit is falling from above or a fine spray of urine rains down on your head, you will know you are close!

White-cheeked Gibbon

Genus and species: Nomascus leucogenys

Distribution and Habitat

White-cheeked gibbons are found in Laos, Vietnam, and southern China in evergreen tropical rainforests and monsoon forests.

Gibbons have a home range of about 75 to 100 acres (0.3 to 0.4 km2) and travel about one mile (1.6 km) per day through this range. They defend approximately three-quarters of their range as their group territory. Defense takes the form of calls from the center of the territory, calls from the boundaries, confrontations across the boundaries, chasing across the boundaries, and, rarely, physical contact between males. Gibbons are arboreal and spend most of their time in the canopy. They rarely stay on the ground for very long. Here at the Zoo the gibbons spend more time on the ground. You may see youngsters wrestling in the grass.

Physical Description

White-cheeked gibbons are 18 to 25 inches (47 to 64 cm) tall and weigh about 15 to 20 pounds (7 to 9 kg). Our females are slightly heavier than males, which is not typical of gibbons in the wild. They exhibit sex- and age-linked color dimorphism. All infants are a beige color. By the time they are one to one and a half years old, their coat has become black with white cheek patches. At sexual maturity (five to seven years), males remain black and females become a beige color again. The external genitalia of males and females are remarkably similar, and the sex of an individual can be hard to determine without close examination. Both sexes have long, dagger-like canines.

Social Structure

Like all gibbons, white-cheeked gibbons live in small, monogamous families composed of a mated pair and up to four offspring. They are physically independent at about three, mature at about six, and usually leave the family group at about eight, though they may spend up to ten years in their family group.

Gibbons are one of the few apes where the adult female is the dominant animal in the group. The hierarchy places her female offspring next followed by the male offspring and finally by the adult male.

Gibbons are one of the few apes where the adult female is the dominant animal in the group. The hierarchy places her female offspring next followed by the male offspring and finally by the adult male.

Grooming is an important social activity between adults, between sub-adults, and between adults and young. Infant centered play behavior is another common social activity.

Communication

Vocalization (see gibbon communication information) is a major social investment. The basic pattern is an introductory sequence where both male and female “warm up,” followed by alternating sequences of male and female calls and of female great calls, usually with a male coda at the end. Calls are often accompanied by behavioral acrobatics.

Reproduction and Development

The menstrual cycle is 28 days, and the gestation period is seven months. White-cheeked gibbons give birth to a single offspring every two or three years. Infants cling to their mothers from birth. Newborns are often found clinging horizontally across the female's abdomen. This allows the mothers to sit with their knees up as most gibbons do. Older infants orient vertically on the abdomen. Youngsters are weaned early in their second year. Once the offspring reach full maturity they usually leave the family group and search for a territory and mate of their own.

Diet in the Wild

White-cheeked gibbons eat mostly ripe fruits, leaves, and a small amount of invertebrates. Fruit eating occupies about 65 percent of feeding time and young leaf eating about 35 percent of feeding time. They move and feed mainly in the upper and middle levels of the canopy and almost never come down to the ground. Families often feed together in the trees.

Distribution and Habitat

White-cheeked gibbons are found in Laos, Vietnam, and southern China in evergreen tropical rainforests and monsoon forests.

Gibbons have a home range of about 75 to 100 acres (0.3 to 0.4 km2) and travel about one mile (1.6 km) per day through this range. They defend approximately three-quarters of their range as their group territory. Defense takes the form of calls from the center of the territory, calls from the boundaries, confrontations across the boundaries, chasing across the boundaries, and, rarely, physical contact between males. Gibbons are arboreal and spend most of their time in the canopy. They rarely stay on the ground for very long. Here at the Zoo the gibbons spend more time on the ground. You may see youngsters wrestling in the grass.

Physical Description

White-cheeked gibbons are 18 to 25 inches (47 to 64 cm) tall and weigh about 15 to 20 pounds (7 to 9 kg). Our females are slightly heavier than males, which is not typical of gibbons in the wild. They exhibit sex- and age-linked color dimorphism. All infants are a beige color. By the time they are one to one and a half years old, their coat has become black with white cheek patches. At sexual maturity (five to seven years), males remain black and females become a beige color again. The external genitalia of males and females are remarkably similar, and the sex of an individual can be hard to determine without close examination. Both sexes have long, dagger-like canines.

Social Structure

Like all gibbons, white-cheeked gibbons live in small, monogamous families composed of a mated pair and up to four offspring. They are physically independent at about three, mature at about six, and usually leave the family group at about eight, though they may spend up to ten years in their family group.

Gibbons are one of the few apes where the adult female is the dominant animal in the group. The hierarchy places her female offspring next followed by the male offspring and finally by the adult male.

Gibbons are one of the few apes where the adult female is the dominant animal in the group. The hierarchy places her female offspring next followed by the male offspring and finally by the adult male.Grooming is an important social activity between adults, between sub-adults, and between adults and young. Infant centered play behavior is another common social activity.

Communication

Vocalization (see gibbon communication information) is a major social investment. The basic pattern is an introductory sequence where both male and female “warm up,” followed by alternating sequences of male and female calls and of female great calls, usually with a male coda at the end. Calls are often accompanied by behavioral acrobatics.

Reproduction and Development

The menstrual cycle is 28 days, and the gestation period is seven months. White-cheeked gibbons give birth to a single offspring every two or three years. Infants cling to their mothers from birth. Newborns are often found clinging horizontally across the female's abdomen. This allows the mothers to sit with their knees up as most gibbons do. Older infants orient vertically on the abdomen. Youngsters are weaned early in their second year. Once the offspring reach full maturity they usually leave the family group and search for a territory and mate of their own.

Diet in the Wild

White-cheeked gibbons eat mostly ripe fruits, leaves, and a small amount of invertebrates. Fruit eating occupies about 65 percent of feeding time and young leaf eating about 35 percent of feeding time. They move and feed mainly in the upper and middle levels of the canopy and almost never come down to the ground. Families often feed together in the trees.

Sumatran Tiger

Class: Mammalia

Class: MammaliaOrder: Carnivora

Family: Felidae

Species: Panthera tigris

A powerful hunter with sharp teeth, strong jaws, and an agile body, the tiger is the largest member of the cat family (Felidae). It is also the largest land-living mammal whose diet consists entirely of meat. The tiger's closest relative is the lion. Without the fur, it is difficult to distinguish a tiger from a lion, but the tiger is the only cat with striped fur.

Scientists have classified tigers into nine subspecies: Bali, Java, Caspian, Sumatran, Amur (or Siberian), Indian (or Bengal), South China, Malayan, and Indo-Chinese. The first three subspecies are extinct.

Size: Tigers range in size from the diminutive Sumatrans—females weigh between 165 and 242 pounds, and males weigh between 220 and 310 pounds—to the largest mainland tigers, such as Indians—females weigh between 220 and 352 pounds, and males weigh between 396 and 570 pounds. Total length ranges from seven to 12 feet.

Habitat: The tiger's current distribution is a patchwork across Asia, from India to the Russian Far East. Tigers require large areas with forest cover, water, and suitable large ungulate prey such as deer and swine. With these three essentials, tigers can live from the tropical rainforests of Sumatra and Indochina to the temperate oak forest of the Amur River Valley in the Russian Far East.

Diet: Tigers prey primarily on wild boar (Sus scrofa) and other swine, and medium to large deer such as chital (Axis axis), red deer (Cervus elaphus), and sambar (C. unicolor). Where they occur together, tigers also hunt gaur (Bos frontalis), a huge wild cattle. Tigers also kill domestic animals such as cows and goats, and occasionally kill people.

Hunting: The tiger hunts alone, primarily between dusk and dawn, traveling six to 20 miles in a night in search of prey. A typical predatory sequence includes a slow, silent stalk until the tiger is 30 to 35 feet from the selected prey animal followed by a lightening fast rush to close the gap. The tiger grabs the animal in its forepaws, brings it to the ground, and finally kills the animal with a bite to the neck or throat. After dragging the carcass to a secluded spot, the tiger eats. A tiger eats 33 to 40 pounds of meat in an average night, and must kill about once per week. Catching a meal is not easy; a tiger is successful only once in ten to 20 hunts.

Territoriality: An adult tiger defends a large area from all other tigers of the same sex. The primary resource of this territory is food. A female's territory must contain enough prey to support herself and her cubs. A male's territory, additionally, must offer access to females with which to mate. Thus, a male's territory overlaps with that of one to seven females. Male territories are always larger than those of females. But territory size varies enormously and is directly related to the abundance of prey in a given habitat. For instance, Indian tigers in prey-rich habitats in Nepal defend quite small territories: female territories average just eight square miles. At the other extreme, in the prey-poor Russian Far East, Amur tiger female territories average 200 square miles. In both areas, male territories are proportionately larger.

Social Behavior: Except for a mother and her cubs, tigers live and hunt alone. But that does not mean they are not social. Scent marks and visual signposts, such as scratch marks, allow tigers to track other tigers in the area, and even identify individuals. A female tiger knows the other females whose territories abut hers; in many cases, a neighbor may be her daughter. Females know their overlapping males (and vice versa) and probably know when a new male takes over. All tigers can identify passing strangers. So, solitary tigers actually have a rich social life; they just prefer to socialize from a distance.

Reproduction: A male and female meet only briefly to mate. After a gestation of 100 to 112 days, two to three blind and helpless cubs are born in a secluded site under very thick cover. Cubs weigh just over two pounds at birth and nurse until they are six months old. During the next 18 months, they gradually become independent, and at about two years of age strike out alone to find their own territory. Females may establish a territory adjacent to that of their mother, or even take over part of their mother's territory. Adult females generally produce a litter every two years.

Mortality and Longevity: Tigers can live to 20 years of age in zoos but only 15 years in the wild. And most wild tigers do not live that long. Only half of all cubs survive to independence from their mother at about two years of age. Only 40 percent of these survivors live to establish a territory and begin to produce young. The risk of mortality continues to be high even for territorial adults, especially for males, which must defend their territories from other males.

Conservation: The tiger is listed as endangered on the U.S. Endangered Species List and on Appendix I of CITES. Between 5,100 and 7,600 tigers remain in the wild. (Editor's Note: As of 2006, tiger specialists estimate that fewer than 5,000 tigers remain.)

Sulawesi Macaque

(Macaca nigra)

(Macaca nigra)Common Names

Sulawesi crested black macaque, black ape, Celebes ape, Celebes black ape, black Celebes macaque, and crested Celebes macaque. (The Celebes island has been renamed Sulawesi.) Though the common names of the Sulawesi macaque sometimes refer to it as an ape, it is actually a monkey.

Distribution and Habitat

Found in Indonesia, on the extreme northeastern tip of the island of Sulawesi (formerly Celebes) and on several adjacent islands. They are also found on the island of Bacan (or Batjan), where it is believed they were introduced by people.

The island is mountainous and covered with tropical rainforest. The climate is hot, but tempered by sea winds.

Physical Characteristics

Sulawesi macaques have black skin, black hair, compact bodies, very small or almost no external tails, and limbs of equal length. There is a crest of long hairs on the top of their head. Both sexes have ischial callosities (large, bare pads at the base of their tails). Females show a large, pink swelling of these pads around the time of ovulation.

Diet

In the wild, macaques are omnivorous (eating both animals and plants), but are mostly vegetarian. They eat fruit, berries, grains, leaves, insects, and occasionally small vertebrates. They also eat monkey chow, kale, apples, oranges, peanuts, mealworms, crickets, and a variety of other fruits and vegetables.

Life Span

Males reach physical maturity between six and ten years of age, and females around six years. Some macaques have lived more than 40 years in zoos.

Reproduction

Gestation is about six months and one young is produced at a time. The intervals between births range from one to two years.

Social Structure and Activity

Social Structure and ActivitySulawesi macaque groups range from five to 50 individuals or larger. There is little evidence of territoriality, but they may defend the area they occupy at any given time. Groups that have been studied spend more than half their day moving and feeding. Adult males moved and rested more than adult females, but fed, foraged, and socialized less.

There is a range of macaque social behaviors that is easily observed. Behaviors include: lip smacking (a greeting), grimacing, grooming, and mutual embraces.

Conservation

Macaca nigra is an endangered species. These macaques are losing their habitat as rainforests are destroyed on Sulawesi. They are also hunted, both as a source of food and because they sometimes raid crops.

Sloth Bear

Order: Carnivora

Family: Ursidae

Genus and Species: Melursus ursinus

Disheveled in appearance, the sloth bear leads a reclusive life in India's forests, noisily seeking out insects and fruits.

Physical Description: Sloth bears have shaggy, dusty-black coats, pale, short-haired muzzles, and long, curved claws used to excavate ants and termites. A cream-colored "V" or "Y" usually marks their chests. Sloth bears' nostrils can close, protecting the animals from dust or insects when raiding termite nests or bee hives. A gap in their teeth enables them to suck up ants, termites, and other insects.

Size: Sloth bears grow five to six feet long, stand two to three feet high at the shoulder, and weigh from 120 (in lighter females) to 310 pounds (in heavy males).

Geographic Distribution: Most sloth bears live in India and Sri Lanka; others live in southern Nepal, and they have been reported in Bhutan and Bangladesh.

Status: The sloth bear is listed as vulnerable on the World Conservation Union's Red List of Threatened Animals.

Habitat: Sloth bears live in a variety of dry and wet forests, and also in some grasslands, where boulders and scattered shrubs and trees provide shelter.

Natural Diet: When trees are in fruit, usually during the monsoon season, sloth bears dine on mango, fig, ebony, and other fruits, and also on some flowers. However, ants and termites, dug out of their cement-hard nest mounds, are a year-round staple. Also, sloth bears climb trees and knock down honeycombs, later collecting the sweet bounty on the forest floor. Beetles, grubs, ants, and other insects round out their diet. During food shortages, sloth bears will eat carrion. They sometimes raid farm crops.

Natural Diet: When trees are in fruit, usually during the monsoon season, sloth bears dine on mango, fig, ebony, and other fruits, and also on some flowers. However, ants and termites, dug out of their cement-hard nest mounds, are a year-round staple. Also, sloth bears climb trees and knock down honeycombs, later collecting the sweet bounty on the forest floor. Beetles, grubs, ants, and other insects round out their diet. During food shortages, sloth bears will eat carrion. They sometimes raid farm crops.

Reproduction: Sloth bears mate during the hot season—May, June, and July—and females usually give birth to two cubs six to seven months later. Cubs are born in an underground den, and stay there for several months. After emerging from the den, cubs stay at their mother's side for two to three years before heading off on their own.

Behavior: Active mostly at night, the sloth bear is a noisy, busy bear. It grunts and snorts as it pulls down branches to get fruit, digs for termites, or snuffles under debris for grubs and beetles. Sloth bears lead solitary lives, and most are nocturnal. (In protected areas, they may be active during the day.) If threatened, these smallish bears will stand on two legs, brandishing their clawed forepaws as weapons.

A Few Sloth Bear Neighbors

Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris): At the top of the forest food chain, this mighty, endangered cat slinks through the shadows in search of spotted deer and other prey, which sometimes includes sloth bears.

Gaur (Bos frontalis): A massive, forest-dwelling wild ox that lives in small herds and feeds in clearings at night.

Lion-tailed macaque (Macaca silenus): An endangered, black-coated monkey with a distinctive gray mane and dangling tail. Troops of 12 to 20 inhabit tropical evergreen forests in India's Western Ghats mountains.

Great pied hornbill (Buceros bicornis): A vulture-sized black, white, and cream-colored fruit-eating bird with a massive, toucan-like bill.

Fun Facts

Sloth bears are the only bears to carry young on their backs. In the late 1700s, the first Europeans to see sloth bears described them as bear-like sloths due to their ungainly appearance and long claws. The Hindi word for bear—bhalu—inspired the name of Rudyard Kipling's bear character Baloo in The Jungle Book.

Family: Ursidae

Genus and Species: Melursus ursinus

Disheveled in appearance, the sloth bear leads a reclusive life in India's forests, noisily seeking out insects and fruits.

Physical Description: Sloth bears have shaggy, dusty-black coats, pale, short-haired muzzles, and long, curved claws used to excavate ants and termites. A cream-colored "V" or "Y" usually marks their chests. Sloth bears' nostrils can close, protecting the animals from dust or insects when raiding termite nests or bee hives. A gap in their teeth enables them to suck up ants, termites, and other insects.

Size: Sloth bears grow five to six feet long, stand two to three feet high at the shoulder, and weigh from 120 (in lighter females) to 310 pounds (in heavy males).

Geographic Distribution: Most sloth bears live in India and Sri Lanka; others live in southern Nepal, and they have been reported in Bhutan and Bangladesh.

Status: The sloth bear is listed as vulnerable on the World Conservation Union's Red List of Threatened Animals.

Habitat: Sloth bears live in a variety of dry and wet forests, and also in some grasslands, where boulders and scattered shrubs and trees provide shelter.